Abstract

Background and Issues

- Local historical properties including cultural assets are also subjected to major damage in natural disasters. However, immediately after a disaster the response is focused on saving lives and restoring livelihoods, and determining the damage to historical properties such as cultural assets, etc., takes time, so examples have been seen where fragile historical buildings have been lost in the process of recovery and restoration.

- Therefore it is considered that determining the state of transformation of historical city areas that have been damaged in earthquakes will be useful for advance restoration and damage countermeasures in other historical city areas.

- Related research includes that related to recovery and restoration of historical city areas (Takeshi Oyanagi, Mitsuhiko Kawakami (2011), Takahiro Abe (2013)); that related to transformation of historical buildings as a result of disasters (Satoshi Komai, Hiroshi Adachi (1999)); research relating to the target area of this research (Shinmachi and Furumachi, Kumamoto City) (Masaaki Fukuhara (1976), Masaji Nakabayashi, Noriaki Nishiyama (1998), Yuri Goya et al. (2015), and Kei Eto et al. (2017)).

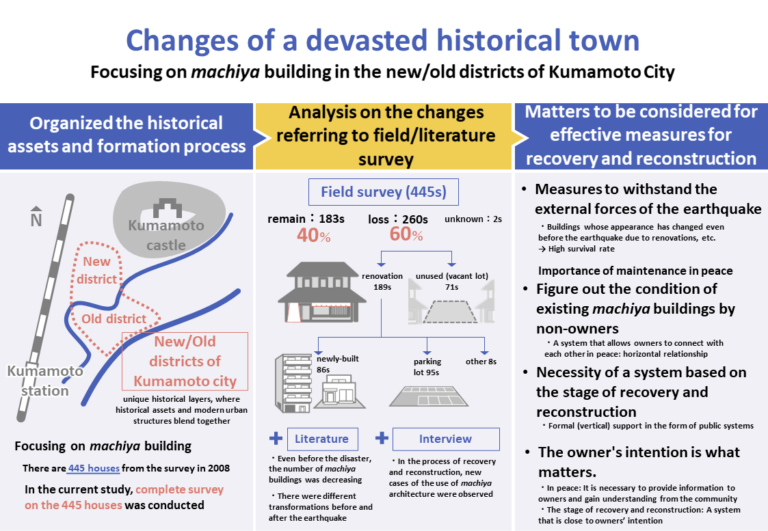

- In this research the state of transformation of a historical city area was determined focusing on both the transformation due to loss of historical properties in a historical city area damaged by an earthquake, and the transformation due to restoration and recovery of the machiya (merchant house) architecture after the disaster.

- The target of the research was the traditional machiya houses in the Shinmachi and Furumachi districts of Kumamoto City, which were damaged in the 2016 Kumamoto Earthquake. In this area recovery and restoration is being carried out, such as preservation of the machiya houses, and regeneration of machiya houses lost in the disaster or the vacant lots of machiya houses that were lost. At the stage that three and a half years have passed since the disaster, the transformation can be seen in the area as a whole in the land use and regeneration on the vacant lots after the destruction, so it was selected as the target of the research.

Data

- Data name

A. “Report of the Shinmachi and Furumachi Area Machiya Pre-Survey Project” (2008)

B. “Machiya Inventory Survey Data for the Shinmachi and Furumachi Area” (2019)

C. “Follow-up Survey of Machiya Houses in the Shinmachi and Furumachi Area, Kumamoto City” (2012)

D. “Amended Shinmachi and Furumachi Survey [Shinmachi] [Furumachi]” (2016)

- Data suppliers

A: Kumamoto Machinami Trust

B: The author (Yutaro Takahashi)

C, D: Ningentoshi Research Institute

- Data recording period

A: 2008

B: July 19-22, 2019 (follow-up survey October)

C: August 27 to September 7, 2012

D: Summer immediately after the 2016 Kumamoto Earthquake

- Data recording content

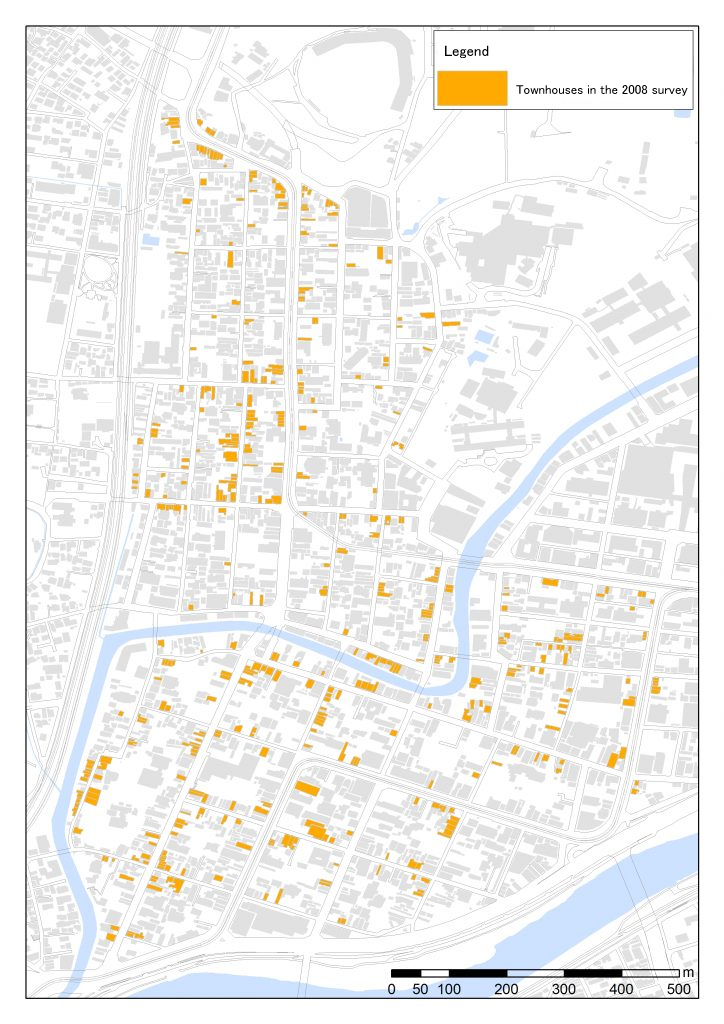

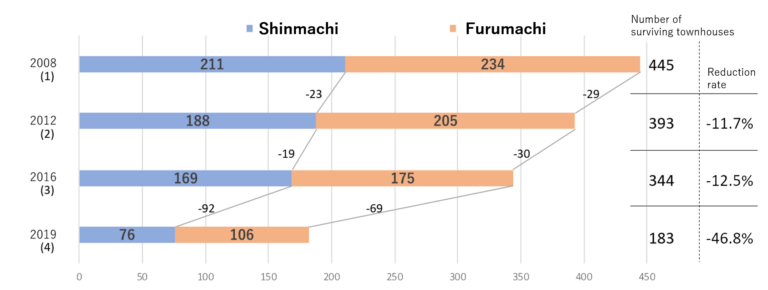

A: A total of 445 machiya houses (211 in Shinmachi and 234 in Furumachi) are shown on the map. For each machiya house photo, the building’s name, use, number of stories and structure, roof materials and members, external walls (front), openings and ornamentation are recorded.

B: The locations of the same 445 machiya houses are shown on the map. For each location, photos, status of survival, use of the lot, state of the machiya house, number of stories, shape of the roof, roof material, and orientation are recorded.

C, D: Status of the same 445 machiya houses

Analysis

- Analysis 1: Changes to the machiya houses: Data sets A and B were compared, and (1) the state of survival of the machiya houses was determined. Also, using data set B, for the machiya house vacant lots, (2) land use, (3) type of car park, and (4) type of new buildings were determined.

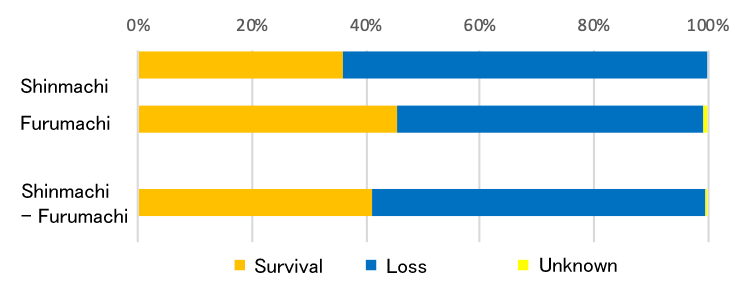

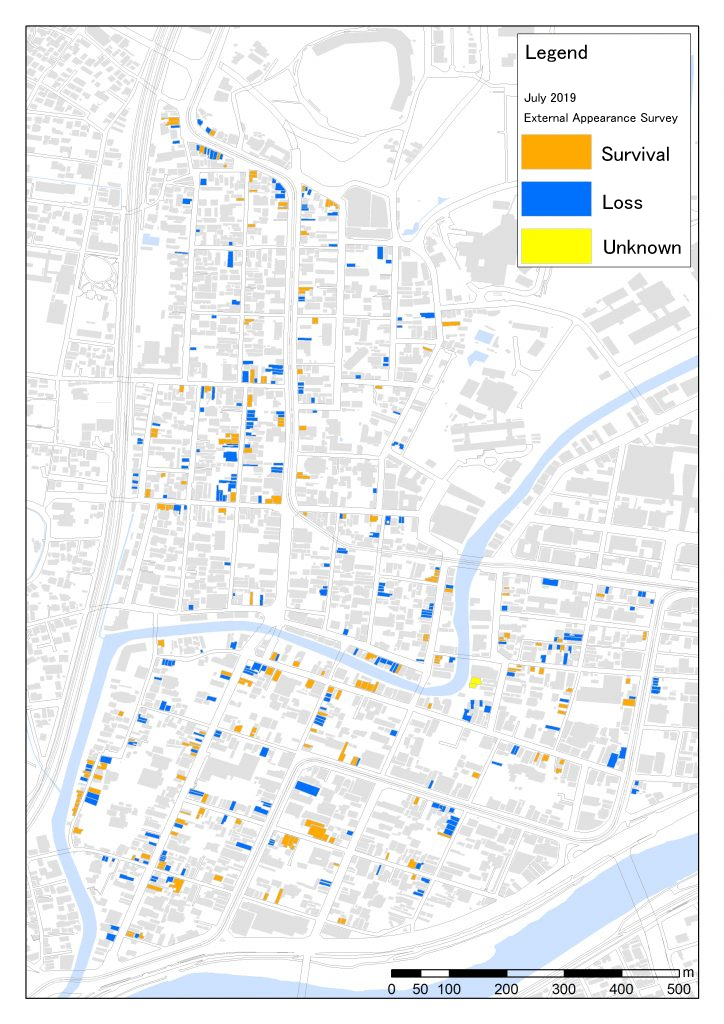

(1) State of survival of the machiya houses

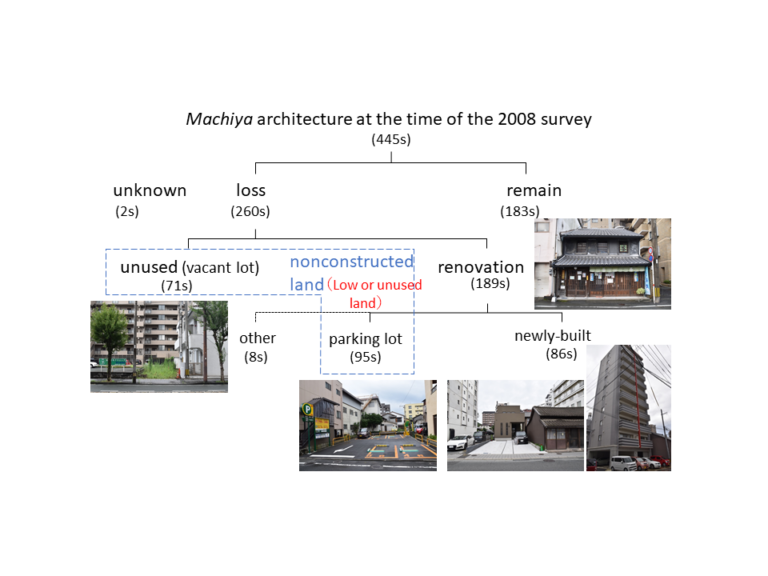

→ The 445 machiya houses confirmed to exist in Shinmachi and Furumachi in 2008 were reduced to 183 by July 2019 as a result of damage due to the Kumamoto Earthquake.

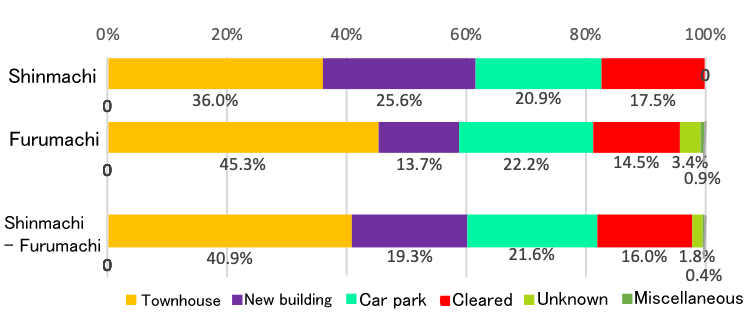

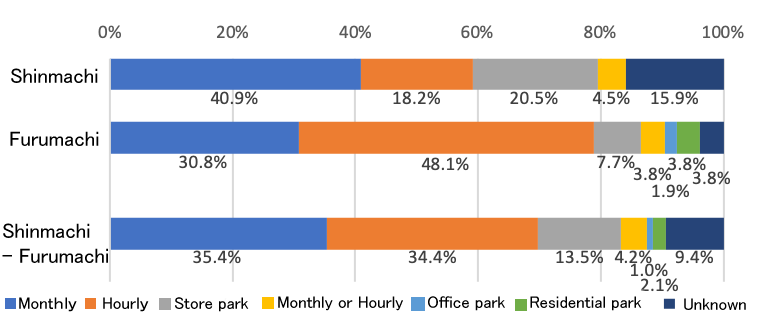

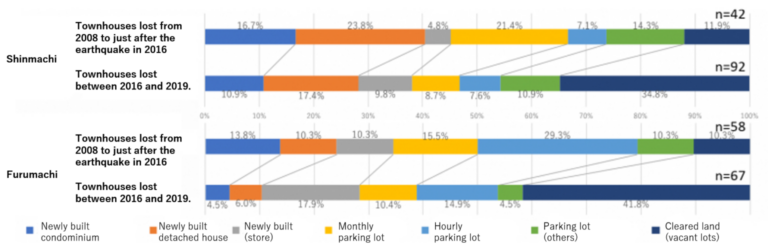

(2) Land use on the machiya house vacant lots

→ The land where the destroyed machiya houses stood has been variously used for new buildings, or car parks, or has been cleared. The loss of the machiya houses that formed the historical scene of the area has transformed the streetscape.

(3) Types of car parks on the machiya house vacant lots

→ In many cases the lots after demolition have been cleared, and the continuity of the streetscape has been lost as a result of the car parks or low use/unused land.

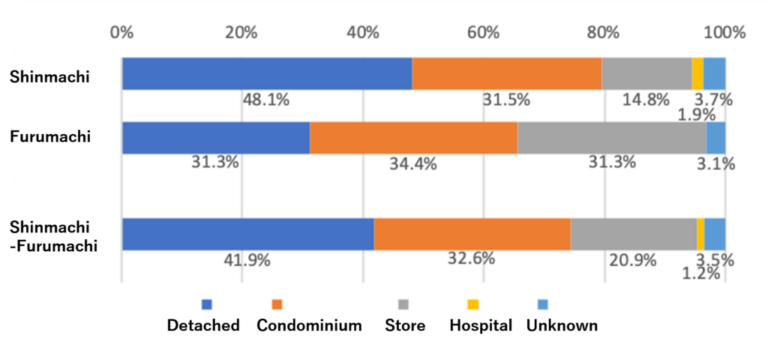

(4) Types of new building on the machiya house vacant lots

→ Construction of large scale condominiums, etc., is in progress on the vacant lots, so the streetscape is changing as a result of the disaster, and even the function of the area is changing greatly.

(5) As a result of analysis 1, the machiya houses existing at the time of the 2008 survey can be classified as shown in the figure as the change at the time of the 2019 inventory survey.

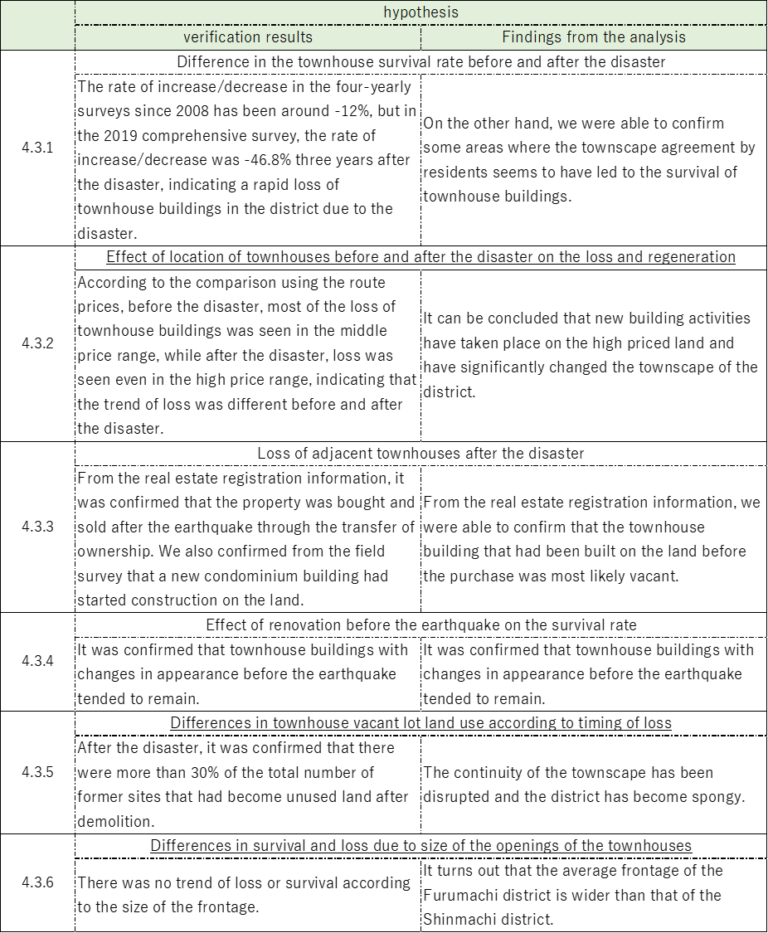

- Analysis 2: Based on the changes found in analysis 1, six factors that affected the transformation of the historic streetscape were proposed and verified: (1) difference in the machiya house survival rate before and after the disaster, (2) effect of location of machiya houses before and after the disaster on loss and regeneration, (3) loss of adjacent machiya houses after the disaster, (4) effect of renovation before the earthquake on the survival rate, (5) differences in machiya house vacant lot land use according to timing of loss, and (6) differences in survival and loss due to size of the openings of the machiya houses.

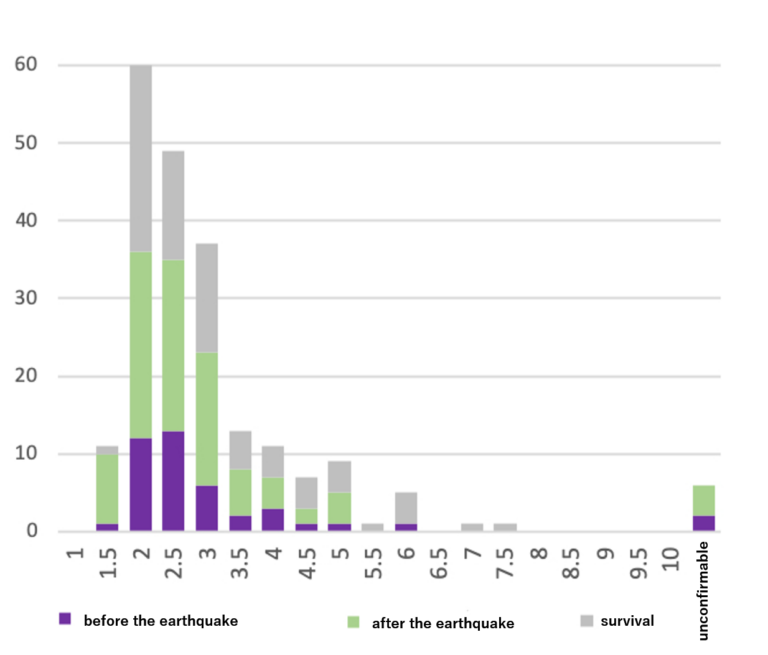

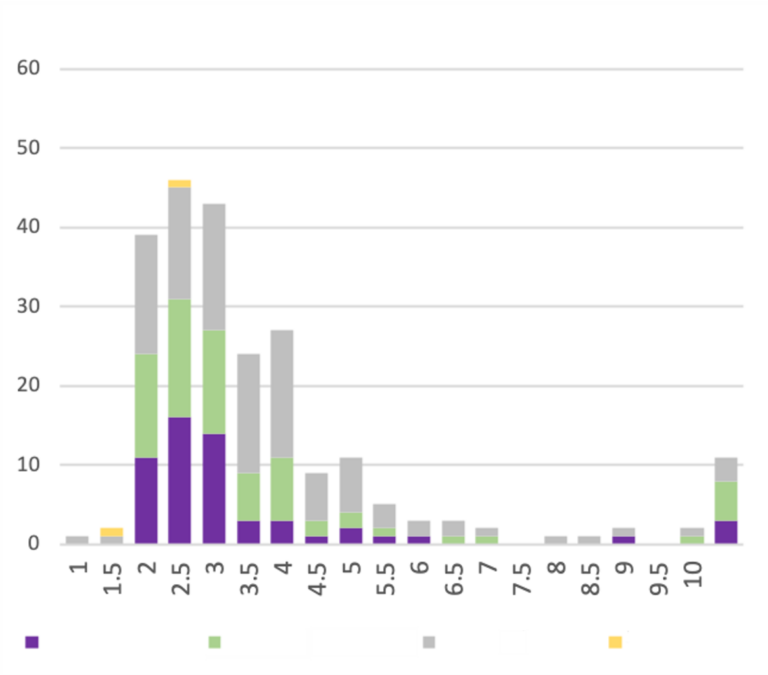

(1) Difference in the machiya house survival rate before and after the disaster

→ The rate of reduction from 2016 to 2019 was 46.8%, so it can be seen that about half of the machiya houses have disappeared since the Kumamoto earthquake.

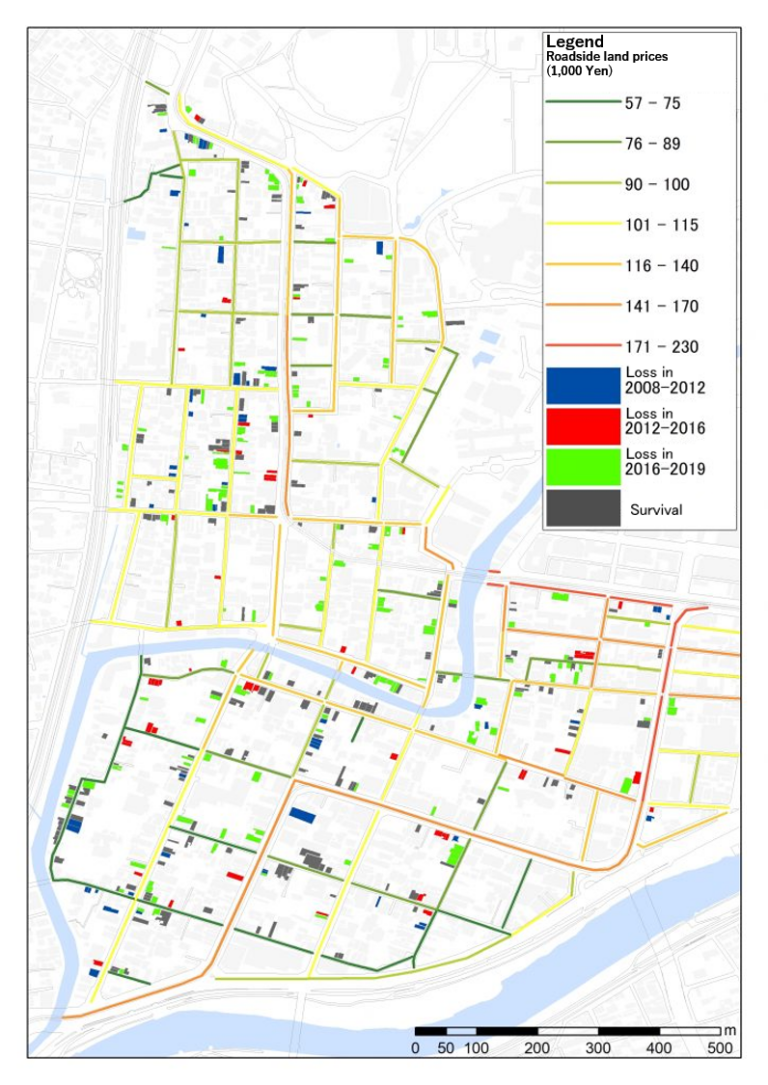

(2) Effect of location of machiya houses before and after the disaster on the loss and regeneration

→ In particular, it has been confirmed that machiya houses were lost after the disaster in good locations, and after demolition new construction is being carried out on the lots, which is a great loss on the historic streetscape of the area.

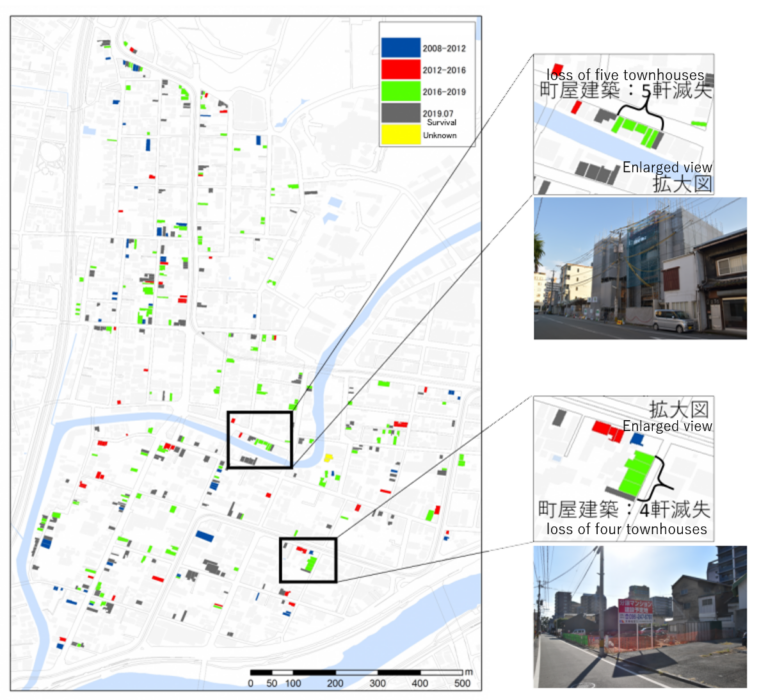

(3) Loss of adjacent machiya houses after the disaster

→ As a result of earthquake damage, adjacent machiya houses were also demolished.

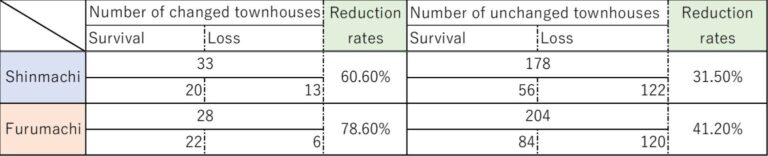

(4) Effect of renovation before the earthquake on the survival rate

Fig. 2-4 Examples of change in external appearance

→ It has been confirmed that the survival rate of the machiya houses that were renovated to harmonize with the streetscape was high.

(5) Differences in machiya house vacant lot land use according to timing of loss

→ It has been confirmed that the land use after loss of the machiya houses after the disaster is mainly cleared land (vacant lots).

(6) Differences in survival and loss due to size of the openings of the machiya houses

→ It is not possible to find a difference in the survival rates before and after the earthquake. If the size of opening of the machiya houses is taken to be representative of their scale, it was not possible to confirm a trend in survival or loss according to the scale of the machiya house.

(7) Verification of hypotheses and summary

The state of transformation of the machiya houses as determined by verification of hypotheses is summarized in the following table.

- Analysis 3: Analysis of the process of recovery and restoration of the machiya houses

(1) Process of recovery and restoration of the area

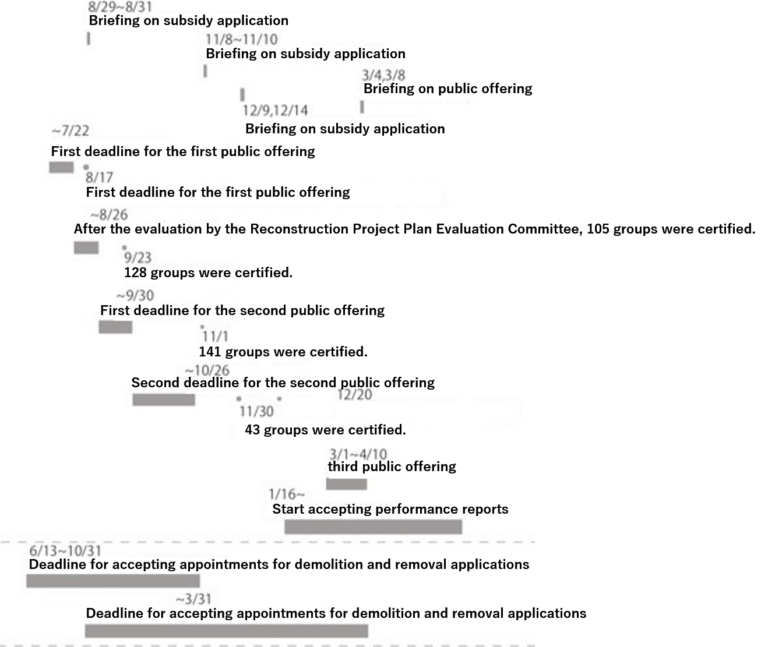

Fig. 3-1 shows the timing of the procedures for the Restoration and Maintenance Subsidy Project for Facilities of Small and Medium Enterprise Groups (group subsidy), and in the lower part the timing of public demolition assistance. During this period, no announcement was made on grant aid for historical buildings, etc., so there is a high possibility that when the owners of machiya houses, etc., were not eligible for group subsidy, they ended up accepting public demolition assistance. Under these circumstances, in March 2017 the prefecture instituted a grant aid system with the purpose of preserving buildings having historical value although they were not designated as such. The project to support the restoration and conservation of the streetscape started in the city in January 2019. Time had passed after the disaster before the system to support historical buildings was instituted, so there were cases in the early stages after the disaster where the group subsidy system was used to preserve machiya houses.

(2) Recovery and restoration of each machiya house

[Example of surviving machiya house: Kiyonaga residence machiya house]

From the occurrence of the earthquake until the start of construction, there was a cooperative local streetscape preservation group and other like-minded machiya house owners that continued to want to preserve the streetscape, and even though it took a lot of time until the start of restoration work, they were encouraged by the prospect of external support or public support. In the area, it is said that because it took so long to announce the framework for support, many machiya houses were demolished, even though there was sentiment to preserve them immediately after the earthquake.

[Example of surviving machiya house: Kitano residence machiya house]

After the disaster the owner met with the present shop owner, and the owner’s wish regarding the use of public support concurred with that of the shop owner’s, so they became resolved during interaction with others met during restoration and recovery activities after the disaster, which led to restoration. At the cafe opening party about 300 people gathered, and the form of a new restoration was seen as a fusion of the owner’s wishes and user’s wishes, as the first symbol of restoration in the area.

[Example of surviving machiya house: Ryoriya residence machiya house]

While both parents had decided on demolition after the disaster, they changed their minds and decided to keep on using the machiya house after their daughter and her husband attended a meeting that reported on site visits to view examples of the use of machiya houses in all parts of the country, held by a restoration project. Prompted by that meeting that reported on the observations, the husband became interested in retaining the machiya house, concurring with the daughter’s feelings that to demolish it would be a waste. It was then decided that the machiya house should be preserved.

→ For each of the machiya houses there was an external person that recognized its value and wanted it to be preserved. Therefore it is considered that bringing these people together will lead to future preservation of machiya houses.

[Examples of demolished machiya houses: Japanese confectionery store “Shiboriya”]

For demolition of the machiya house and new construction, the owner used group subsidy, and did not use public demolition assistance. When they applied for public demolition assistance about 5 months after the disaster, the demolition schedule was June 2017 for witnessing and July for demolition, due to a shortage of workers in the recovery and restoration process, and even then this was not certain. For the owner, who decided to restart the business as soon as possible, waiting for the public demolition assistance was not an option in the construction plan, so they decided to use the group subsidy to defray the demolition cost.

[Examples of demolished machiya houses: soba restaurant “Sarashina”]

For a while the owner was undecided whether to re-open the business after the disaster. However his son that operated a bike shop behind his restaurant had decided to open a restaurant, so 10 months after the disaster they prepared a temporary shop on the site of the bike shop and re-opened business. Public demolition assistance was applied for in December 2016, and demolition was carried out in June 2017. Demolition was carried out by workers from Oita Prefecture. After starting business at the temporary store, applications for group subsidy commenced, and in April 2019 construction of the current store plus residence was completed, and at the end of June business was re-started in the new shop.

→ It is considered that the group subsidy system was made available at an early appropriate stage to effectively promote recovery and restoration together with public demolition assistance.

Results

The four points to note when investigating effective measures for recovery and restoration in historical urban areas obtained in this research from the state of transformation of historical urban areas during the process of recovery and restoration are summarized as follows.

- Measures to withstand the external forces of earthquakes are required. In this research it was found that the survival rate was higher for machiya houses in which modifications that changed the external appearance were made before the earthquake. Therefore it is considered that performing maintenance on machiya houses in normal times minimizes the damage due to a disaster, which enables the machiya houses to be passed on to subsequent generations.

- It is necessary that people other than the owners are aware of the environment and situation of the surviving machiya houses. In this research it was found that people developed horizontal relationships with their peers, which helped them find people whom they could consult, and led to enhanced cohesion. Therefore in order that people other than the owners can understand the environment and situation, it is necessary to establish a mechanism so that in normal times owners connect with each other.

- The necessity and importance of providing systems in accordance with the stages of recovery and restoration. In the Kumamoto earthquake, which were the subject of this research, it is regrettable that the options of public support for both demolition and conservation were not offered at an early stage. In discussions with owners, the opinion was voiced that they ultimately made a decision because support was available, so it is important that public vertical support is appropriately offered.

- The importance of the wishes of the owners. Providing information to owners in normal times and deepening understanding in the area, and providing mechanisms for support in line with their wishes in the process of recovery and restoration result in preservation of historical buildings, and protect the streetscape of historical urban areas from damage due to natural disasters.

References

– Takeshi Oyanagi, Mitsuhiko Kawakami, Reconstruction of Damaged Houses and Consensus Formulating Process to Preserve Townscape in a Seismic Affected Historical District – A case of Kuroshima historical preservation district in Wajima City -, Journal of Architectural Planning, AIJ, Vol. 76, No. 659, pp. 91-99, January 2011

– Takahiro Abe, Basic Study on the Process for Restoration of Historical Urban Areas in a Time of Natural Disaster – Case Studies of Historical Urban Areas Restored from the Natural Disasters in the Past and the Great East Japan Earthquake -, Journal of the City Planning Institute of Japan, Vol. 48, No. 3, October 2013

– Satoshi Komai, Hiroshi Adachi, Research into Conservation and Reconstruction of Historical Buildings After the Hanshin Awaji Great Earthquake, Proceeding of the Architectural Research Meetings of the Architectural Institute of Japan, Kinki Chapter, 965-968, 1999

– Masaaki Fukuhara, The Machiya Houses of Kumamoto City – Their Urban Landscape -, Proceeding of the Architectural Research Meeting of the Architectural Institute of Japan, Kyushu Chapter, No. 22, 309-312, February 1976

– Masaji Nakabayashi, Noriaki Nishiyama, A Study on Understanding The Character of Townscape in The Historic Quarters: A Sample of Furumachi and Shinmachi in Kumamoto City Old Quarters, Proceeding of the Architectural Research Meeting of the Architectural Institute of Japan, Kyushu Chapter, No. 37, 165-168, March 1998

– Yuri Goya, Kazuhisa Iki, Riken Homma, Koki Uchida, Masashi Mochidome, Landscaping guideline by means of impression evaluation in Furumachi district, Kumamoto City, Proceeding of the Architectural Research Meeting of the Architectural Institute of Japan, Kyushu Chapter, No. 54, 497-500, March 2015

– Kei Eto, Kazuhisa Iki, Riken Homma, Syota Sasaki, Research into the Preservation and Utilization of Machiya Houses in Earthquake Disaster Restoration – Case Study from Shinmachi and Furumachi in Kumamoto City -, Proceeding of the Architectural Research Meeting of the Architectural Institute of Japan, Kyushu Chapter, No. 56, 225-228, March 2017