Abstract

Background and issues

Amid the rapidly increasing introduction of renewable energy as a result of the full-scale introduction in July 2012 of feed-in-tariff (FIT), a system of fixed-price purchase of renewable energy, the bottom-up policy of using local renewable energy resources (renewable energy) aimed particularly at the revitalization of farming and mountain villages, in other words, an energy transformation originating in local communities, is gaining attention.

An important role is being played by the cities, wards, towns, and villages that constitute municipalities, which are most closely positioned to look at the reality faced by local communities. We compiled renewable energy policies by municipalities from the 2014 part of the Fact-Finding Survey on Renewable Energy in Municipalities Nationwide carried out in 2014 and 2017 by Asahi Shimbun Company (referred to as the “questionnaire survey”), which is part of Hitotsubashi University’s natural resources economics project (Table 1).

| Classification | Type of policy (abbreviated) |

| Policies that promote the introduction of renewable energy, regardless of type | Municipalities that promote renewable energy under documented policies by means of regulations, plans, targets, “new energy visions”, and others (documented promotion of renewable energy) Development of administrative plans and regulations (plans/regulations) |

| Policies mostly focused on the introduction of solar power | Subsidies and grants for the installation of renewable energy facilities (facilities installation subsidies) Installation of solar panels by the municipalities themselves (voluntary installation of solar power) Leasing pubic land and roofs of public facilities to companies engaged in renewable energy (public land and roof leasing) (Land and housing support) |

Municipalities are promoting the introduction of renewable energy through various renewable energy policies. Some municipalities have achieved a significant increase in the introduction of renewable energy, and others have not.

So far, no research has been reported which considers the entire country in analyzing and evaluating in an empirical manner the relation between the status of implementation of renewable energy policies and the amount of renewable energy introduced at the level of municipalities, taking into consideration the municipalities’ background factors of geographical and socio-economic attributes.

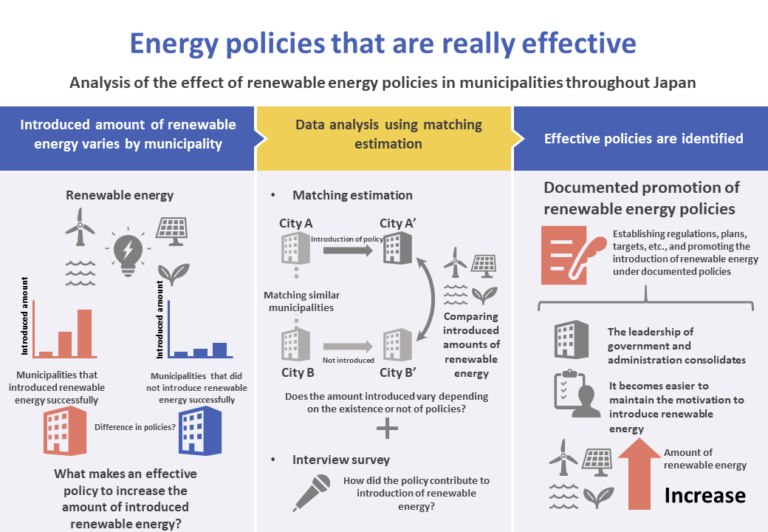

- In the present research, we predict the effects of the six renewable energy policies listed in Table 1, by analyzing questionnaire surveys in a quantitative investigation, combining data related to renewable energy policies, data related to the natural environment, and data concerning financial, socio-economic, and political factors for municipalities throughout Japan. We also conduct an interview survey in Hanamaki city, to investigate qualitatively how the policies contribute to increasing the amount of renewable energy introduced.

- In this way, we expect to contribute to the development of effective renewable energy policies led by local communities.

Data analysis

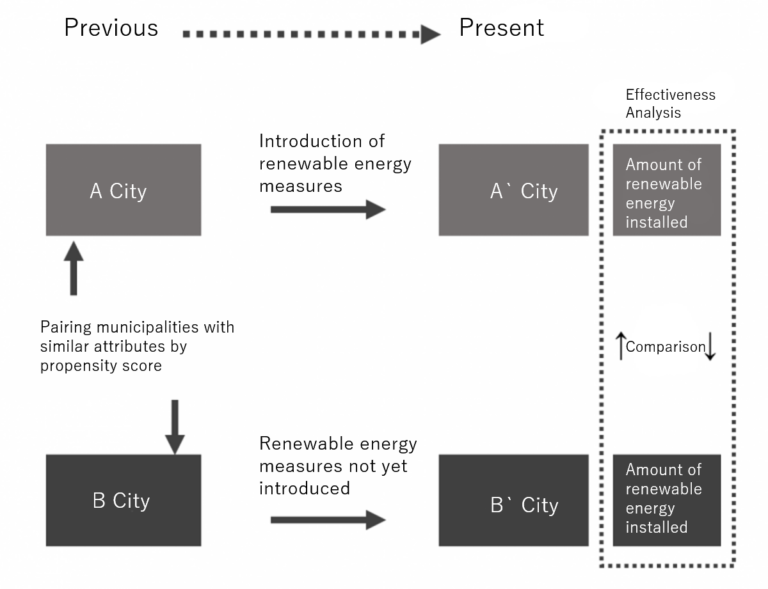

The ideal way to test the effects of a renewable energy policy is to contrast the amount of renewable energy introduced by a municipality in the case where the policy is introduced against the case where it is not. However, that is not realistic. Instead, we compare a municipality that has introduced such a policy with another municipality exhibiting similar attributes which has not introduced a policy, using a method called matching estimation (Figure 1).

The matching of municipalities is based on the proximity of estimated propensity scores. In the present research, the propensity score expresses the probability of introducing each renewable energy policy in each municipality. The objective of the propensity score is only to adjust the background factors of municipalities.

Considering the multiple attributes involved in the introduction of renewable energy policies by municipalities, we use a logit model for estimating propensity scores with explanatory variables such as the financial power of the municipality, the opulence of the region, population, the potential for using renewable energy (renewable energy potential), the proportion of workers in the primary industry, political factors (dominance of the ruling political party), as well as city/ward dummies and prefecture dummies.

A robustness issue in matching estimation is that combinations may change according to the order in which the municipalities are taken, especially for types of renewable energy with few case examples. For this reason, a doubly robust estimator is also calculated for two items, “documented promotion of renewable energy” and “plans/regulations”, which have relatively few case examples.

Moreover, because of the importance of defining a period with a fixed start and end, to measure the amount of renewable energy introduced (increase), we establish individual measuring periods for solar and wind power, small and medium-sized hydroelectric power, and several types of biomass power.

Evaluation and demonstration

The matching estimation analysis indicated that the only policy among those included in “policies that promote the introduction of renewable energy regardless of type” that contributed to increasing the introduced amount of renewable energy of a wide range of types was “documented promotion of renewable energy”.

It became clear that those municipalities that took a positive attitude in promoting renewable energy, mostly by means of institutional design, were the ones that contributed the most to increasing the introduced amount of renewable energy. This was demonstrated by the boost achieved by the introduction of solar power, wind power, small and medium-sized hydroelectric power plants, methane fermentation gas, and biomass energy such as general woody biomass in such municipalities.

It was shown that “plans/regulations” contributed to boosting the introduction of mega-solar and small or medium-sized hydroelectric power plants, but the doubly robust estimators showed the difficulty in concluding that such contribution covered a wide range of types of renewable energy.

Among the “policies mostly focused on the introduction of solar power”, the effects of the “facilities installation subsidies” and “voluntary installation of solar power” policies had no effect according the analysis based on matching estimation, despite the fact that they have been implemented by a large number of municipalities.

Concerning the former, it is expected that the lower prices resulting from the popularization of solar power generation equipment and the perspective of stable profits arising from the selling of electric power enabled by FIT provided a greater economic incentive than the target policies themselves. As for the latter, we consider that one of the main causes is that the amount of power introduced by municipalities is limited in quantity, compared to the introduction of solar power by the private sector in houses and businesses.

It was shown that two policies, “public land and roof leasing” and “land and housing support”, contributed to boosting the introduction of low-power solar energy.

Moreover, the results above indicate that municipalities contribute more in terms of the total amount of introduced renewable energy in the entire region by applying existing assets (public land, public facilities, and the like) in cooperation with private companies, rather than by installing new renewable energy facilities.

Interview survey with Hanamaki City, Iwate Prefecture

In order to conduct a qualitative investigation on the role and effect produced by documented promotion of renewable energy during the policymaking process, we investigated the case of Hanamaki City in Iwate Prefecture. The city exhibits an extremely high propensity score regarding documented promotion of renewable energy, but in fact is not performing that kind of documentation.

As of 2014, Hanamaki City was engaged in three renewable energy policies: “facilities installation subsidies”, “voluntary installation of solar power”, and “land and housing support”. As of today, all policies except for “voluntary installation of solar power” have been concluded, and no other policy has been started since 2014.

We conducted interviews to investigate the connection between this situation and the fact that the documented promotion of renewable energy did not take place. We learned that an effort was made towards the documented promotion of policies in 2015 (the tentative formulation of a new energy vision), but it did not become a reality.

We then asked about the hypothetical positioning of environmental or renewable energy policies, if the documentation of such policies did occur. The answer was that the Hanamaki City Anti-Global Warming Plan and the New Energy Vision (tentative) would exist in parallel, under the Hanamaki City Basic Environmental Plan.

From the above, we gained the impression that if a documented elaboration of policies did occur, the expected effect on the formulation of policies would be “to play a progress management role for renewable energy policies, resulting in the effect of promoting renewable energy”.

Results and proposal

Among the policies included in “Policies that promote the introduction of renewable energy, regardless of type”, “documented promotion of renewable energy” and “development of administrative plans/regulations” were estimated to be effective. In particular, the former was the only one that contributed to increasing the amount of introduced renewable energy for a wide range of types.

These results indicate the difficulty in evaluating the effect of policies for a wide range of types of renewable energy other than solar power, in the narrower sense of “development of administrative plans/regulations”, compared to the broader concept of “documented promotion of renewable energy”.

Within “policies mostly focused on the introduction of solar power”, “leasing pubic land and roofs of public facilities to companies engaged in renewable energy” and “land and housing support” were estimated to be effective. No statistically significant effect was estimated in the effects of two policies adopted by a large number of municipalities: “subsidies and grants for the installation of renewable energy facilities” and “installation of solar panels by the municipalities themselves”.

The interviews with Hanamaki City in Iwate Prefecture showed that documentation aids management of the progress of existing projects and policies, helping to maintain the motivation for renewable energy policies, and contributing to increasing the amount of renewable energy introduced in the whole region.

According to these results, based on both quantitative and qualitative investigation, documented promotion of renewable energy policies contributes to solidifying the leadership of Government and Administration, which are the highest platforms for local energy policies, thus increasing the amount of renewable energy introduced in the region.